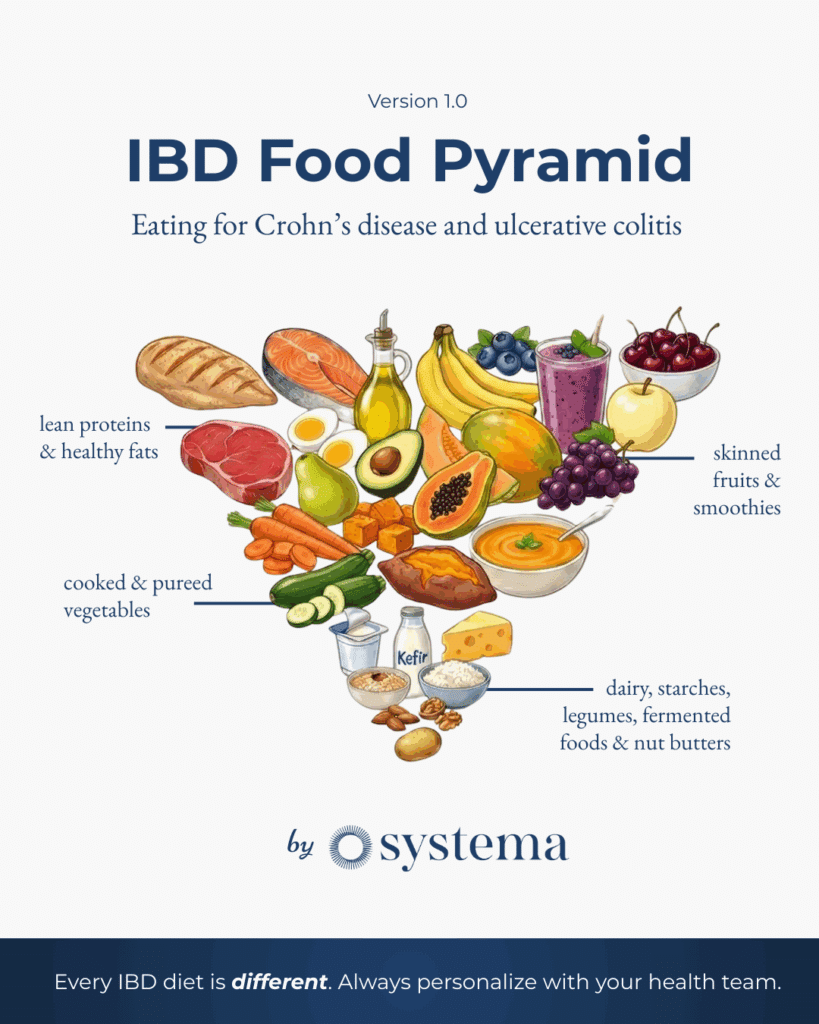

A science-based & IBD expert developed visual framework for nutritional navigation with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis

by Systema Health

Let me say this right from the start: There is no one IBD diet.

I know that’s probably not what you wanted to hear. You’re likely searching for a simple list of foods to eat and foods to avoid. I get it. After my Crohn’s diagnosis at 16, I spent years desperately searching for the same thing.

But here’s what I’ve learned from working with hundreds of people with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis: every single one of you is biologically unique. You have unique microbiomes, unique inflammatory triggers, unique cultural backgrounds, unique financial situations, and unique food preferences. What sends one person into a flare might be perfectly tolerated by another[1,2].

That said, there are science-backed principles that can guide your dietary choices. There are foods that tend to support healing and foods that tend to promote inflammation[3,4].

That’s why we created the IBD Food Pyramid.

Introducing the IBD Food Pyramid

You’ll notice this isn’t your grandmother’s food pyramid. We’ve designed it specifically for people with inflammatory bowel disease, based on what we know about gut healing, inflammation, and the microbiome.[5,6]

The pyramid puts what most IBD patients should prioritize at the top (the widest section) and what requires more individualized caution at the narrow bottom. Let’s walk through each tier.

Systema’s Four Dietary & Nutritional Principles

Before we dive into the pyramid, here are the core principles that guide everything we teach:

Principle 1: Eat real, nutrient-dense, whole foods and avoid processed and artificial ingredients.[7,8]

Principle 2: Your diet is completely unique. Only you can determine what fits your unique biology, needs, and desires.[1,9]

Principle 3: Your mental health and well-being around food is just as important as the diet you’re following.[10]

Principle 4: You must go through a strategic process to design and test your own diet to truly determine what you do and don’t eat in the context of your current state of health.[11,12]

With these principles in mind, let’s explore the pyramid.

Tier 1: Lean Proteins & Healthy Fats

The foundation of gut-friendly eating for Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.

At the top of our pyramid, you’ll find lean proteins and healthy fats. These are foods that most people with IBD tolerate well and that provide essential building blocks for healing.[13,14]

Why Proteins Matter

When you have IBD, your body is working overtime to repair damaged intestinal tissue. Protein provides the amino acids needed to rebuild.[15,16] Many people with IBD are also at risk for protein malnutrition due to malabsorption.[17,18] Research shows sarcopenia (muscle wasting) is significantly more prevalent in IBD patients compared to the general population.[19,20]

Proteins (Incorporate with intention):

- Lower mercury seafood (salmon, sardines, mackerel): Rich in omega-3 fatty acids that actively fight inflammation.[21,22] Research shows EPA and DHA help reduce inflammation that may otherwise lead to chronic health conditions.[23,24,25]

- Pasture-raised poultry: Lean, easily digestible, versatile (often a very neutral protein).[14]

- Grass-fed meats:* In moderation for some; provides iron, zinc, and B12. Leaner cuts are generally better tolerated.[26] *if in your budget, otherwise grain fed is acceptable

- Pasture-raised eggs: Well-tolerated by many; excellent protein source.[27] Can be inflammatory for some, so mind your symptoms.

- Organ meats and bone broth:* Micronutrient powerhouses that support gut healing.[28,29] Bone broth provides glycine and collagen peptides that may support intestinal barrier function.[30,31] *as tolerated and depending on the availability.

Why Healthy Fats Are Essential

Not all fats are created equal. The right fats reduce inflammation; the wrong ones fuel it.[32,33]

Prioritize:

- Extra-virgin olive oil: Rich in polyphenols and oleocanthal, which acts similarly to ibuprofen in fighting inflammation.[34,35] Use raw or at low heat. Studies show olive oil polyphenols support gut barrier function.[36]

- Avocado and avocado oil: Monounsaturated fats that support gut health in moderation.[37,38]

- Ghee/clarified butter: Often tolerated even by those sensitive to dairy.[39] Contains butyrate, a short-chain fatty acid that supports intestinal health.

- Omega-3s from fish: Directly suppress inflammatory pathways.[21,22,40]

- Animal fat like beef tallow: in moderation

Tier 2: Skinned Fruits & Smoothies

Nature’s anti-inflammatories, prepared for gut healing.

Colorful fruits deliver powerful healing compounds, but preparation matters when you have IBD.[41]

Dark Fruits and Berries

Dark fruits and berries are powerhouses of nutrition, packed with anthocyanins, flavonoids, and polyphenols. These are potent anti-inflammatory compounds.[42,43]

Examples: Blueberries, blackberries (careful b/c of seeds), raspberries, pomegranates (highest antioxidant activity), acai berries, cherries, grapes, bilberries

Key benefits:

- High antioxidant activity [44,45]

- Prebiotic effects from flavonoids and polyphenols[46,47]

- Microbiome-supporting fibers[48]

- Polyphenols may even promote neuroplasticity[49]

IBD-specific tip: During flares, blend berries into smoothies and strain out seeds. Watch for berry skins, which can be bothersome for some. The anti-inflammatory compounds remain even when texture is modified.[5]

Tropical Fruits

Tropical fruits offer unique nutritional benefits, particularly digestive enzymes and specific fibers that support gut health.[50] They contain gelatinous fibers that can be particularly beneficial for the microbiome.

Examples: Papaya (rich in papain, a digestive enzyme)[51], pineapple (contains bromelain)[52,53], mango, kiwi, banana[54], lychees, dragon fruits, passion fruit (strain seeds)

Key benefits: Digestive enzymes, fiber, gut health support, vitamins and minerals[50,51,52]

Smoothies: Your Secret Weapon

Smoothies allow you to pack in nutrition while keeping texture gentle on your gut. A well-designed smoothie can deliver anti-inflammatory berries, healthy fats, protein, and gut-soothing ingredients.[5,41]

A Note on Citrus

While citrus fruits contain vitamin C and beneficial compounds, the acidity can irritate inflamed intestinal tissue. During flares, stick to lemons and limes in juice form only. As you heal, you can explore whole citrus more freely.

Tier 3: Cooked & Pureed Vegetables

Here’s where texture becomes your secret weapon.

Vegetables are nutritional powerhouses. But here’s what most IBD diet guides miss: how you prepare vegetables matters as much as which ones you eat.[5,55]

The Texture Principle

Think about this: if you have active IBD, you literally have wounds inside your intestines. You wouldn’t rub rough sandpaper on a wound on your skin, would you?

The American Gastroenterological Association’s 2024 Clinical Practice Update specifically recommends that patients with IBD may not tolerate fibrous, plant-based foods due to their texture. They advise cooking and processing fruits and vegetables to a soft, less fibrous consistency [5]. This approach is supported by evolving clinical guidance that emphasizes texture modification over fiber restriction.[55,56]

The Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation explains it beautifully: raw kale and blended kale contain the same nutritional value, but blended kale is much better tolerated because it acts more like soluble fiber in the intestines.[57]

During active flares, this phase may resemble the diet of a 9-month-old infant. Soft, pureed, easily digestible. That’s okay. It’s temporary.

The Cucurbitaceae Family (Squash, Zucchini, Pumpkins etc.)

These are some of the most gut-friendly “vegetables” you can eat (botanically they are actually fruits but we prepare them as vegetables). Their soft, soluble-fiber flesh makes them ideal during flares and foundational phases.[58,59]

Examples: Zucchini, yellow squash, butternut squash, acorn squash, pumpkin, spaghetti squash, cucumber (peeled/seeded)

Key: These cook down to very soft textures and are naturally low in insoluble fiber. Roast, steam, or blend into soups.

Root Vegetables and Alliums (Onions, Garlic etc.)

Root vegetables and alliums offer a wealth of nutrients and unique health benefits. Alliums (onions, garlic) are rich in unique prebiotic fibers that feed beneficial gut bacteria [60,61]. Those sensitive to FODMAPs may need to limit alliums[62,63,64].

Examples: Carrots[65], parsnips, beet [66], sweet potatoes[67], onions, shallots, garlic, leeks

Key: Cook until very soft. During flares, peel and puree.

🥬 Leafy Greens and Cruciferous Vegetables (Proceed with much caution)

Leafy greens and cruciferous vegetables are nutrient-dense, rich in vitamins, minerals, and beneficial plant compounds. However, their high insoluble fiber content and tough cell walls can be problematic for many with active IBD[55,56,68].

Examples: spinach, broccoli, cauliflower, chard (be very careful with kale, collard greens, you need to cook them very well if you decide to eat them)

Key: These are not essential during flares or foundational phases. If you include them, cook thoroughly, blend or puree, and introduce slowly in small amounts. Many people with IBD do better minimizing or avoiding these until stability is achieved or even avoiding them altogether.

Research on sulforaphane from broccoli sprouts shows promise for gut health when properly prepared[69,70,71].

🍄 Mushrooms (Nourishing with intention)*

*always cook and blend

Mushrooms occupy their own kingdom — neither plant nor animal — and offer unique compounds you simply can’t get elsewhere. They’re rich in beta-glucans, polysaccharides that support immune function in ways particularly relevant to autoimmune and autoinflammatory conditions like IBD[72,73,74].

Culinary mushrooms:

- Button, cremini, portobello (same species, different maturity)

- Shiitake — rich in lentinan, an immune-modulating compound[75,76]

- Oyster mushrooms — good source of protein and B vitamins

- Maitake (hen of the woods) — studied for immune support[74]

- Chanterelles — prized for flavor, rich in vitamins D and B, and antioxidants

- Morels — nutrient-dense with high protein content; always cook thoroughly (toxic when raw)

Medicinal mushrooms:

- Lion’s Mane: Research suggests benefits for gut health and the gut-brain axis[77,78]

- Reishi: Traditional “mushroom of immortality” with anti-inflammatory properties[79]

- Chaga: High in antioxidants

- Turkey Tail: Contains PSK and PSP, well-studied immune modulators[80,81]

Key benefits:

- Beta-glucans support balanced immune function[72,73]

- Good source of B vitamins and selenium

- One of the few non-animal sources of vitamin D (when UV-exposed)[75]

- Unique prebiotic fibers that support beneficial gut bacteria

IBD tip: Those with digestive sensitivities should cook mushrooms thoroughly — this breaks down tough cell walls and improves digestibility. Blending cooked mushrooms into soups or sauces can make them even gentler. Start with common culinary varieties before exploring medicinal mushrooms.

Caution: Only consume wild mushrooms identified by experts. Some are toxic. When in doubt, stick to cultivated varieties.

Vegetable Texture Guide by Phase

| Phase | Preparation |

| Active Flare | Do not consume mushrooms |

| Foundational | Cooked well, blend as needed, peeled |

| Stability | Cooked, whole textures okay |

| Exploratory | All preparations tolerated |

Tier 4: Dairy, Starches, Legumes, Fermented Foods & Nut Butters

This is where personalization becomes critical.

At the narrow base of our pyramid sit foods that require the most individualized approach. These aren’t “bad” foods. They’re simply foods where tolerance varies dramatically from person to person[1,5,9].

🤔 Dairy: A “Maybe” Food for Most

Dairy tolerance is highly individual in IBD[82,83]. Research shows lactose malabsorption is more prevalent in IBD patients[84,85].

Consider trying:

- Goat and sheep products: Often better tolerated than cow dairy due to different protein structures and fat globule sizes[86,87]

- Fermented dairy (yogurt, kefir): May support gut health through probiotics[88,89]

- Hard, aged cheeses: Lower in lactose due to aging process

- Lactose-free options

- A2 dairy: Some research suggests A2 beta-casein may be gentler than A1[90,91]

During foundational phase: Many do best avoiding cow dairy entirely. Goat/sheep products 0-2x per week if tolerated.

🤔 Starches and Grains: Proceed Strategically

Here’s why starches sit at the bottom of our pyramid:

Complex carbohydrates that aren’t absorbed in the small intestine travel to the colon where they’re fermented by bacteria. In a dysbiotic gut (common in IBD), this can feed problematic bacteria and worsen symptoms[92,93]. This is why the Specific Carbohydrate Diet and similar approaches have helped many achieve remission[94,95,96]. When you exclude these foods you are in many respects “modulating” the microbiome, hallmark two of our second step of remission “Modulate and Nourish the Microbiome.”

If you include starches:

- Prioritize: Sweet potatoes[67] over well-cooked rice, quinoa, oats*

- Consider limiting during active disease: Wheat, corn, white potatoes (however white potatoes do contain a small amount of powerful fiber)

- Fermented grains: True sourdough bread may be better tolerated[97,98,99]

*Pro tip: Cooking and cooling starchy foods creates “resistant starch,” which feeds beneficial bacteria[100,101,102]. Potato salad may be better tolerated than a hot baked potato (don’t eat seed oils in your potato salad please). You can go through a process of heating and cooling and then consuming your starches at a warm or cold temperature.

A Note on Gluten

Gluten deserves special attention for people with IBD — even those without a celiac diagnosis.

Research shows that gluten sensitivity exists on a spectrum[103,104]. You can experience inflammatory responses to gluten without having celiac disease. Studies suggest that a significant portion of IBD patients report improvement when reducing or eliminating gluten, even when celiac has been ruled out[105,106,107].

If you choose to include gluten:

- Prioritize true sourdough: Traditional long-fermented sourdough (24-48 hours) partially breaks down gluten proteins and may be better tolerated[97,98,108]. The fermentation also creates beneficial compounds for gut health and reduces FODMAPs[99]. Note: Most commercial “sourdough” isn’t truly fermented — look for artisan bakeries or make your own.

- Choose ancient grains: Einkorn, spelt, and emmer contain different gluten structures than modern wheat and may be gentler for some[109].

- Read labels carefully: Gluten hides in unexpected places — soy sauce, salad dressings, medications, and supplements.

During foundational phase: Consider eliminating gluten entirely for 4-6 weeks, then reintroduce strategically to assess your personal tolerance. Many if not most people with IBD do not tolerate gluten well.

🫙 Fermented Foods: Powerful but Personal

Fermented foods deserve their own conversation. They’re far too beneficial to dismiss, but tolerance varies significantly from person to person.

The science is compelling: Stanford research found that a diet rich in fermented foods enhances the diversity of gut microbes and decreases molecular signs of inflammation[110]. For many people with IBD, this is exactly what we’re looking for.

Fermented foods include:

- Vegetables: Sauerkraut, kimchi, lacto-fermented pickles

- Dairy: Yogurt, kefir (if tolerated)[88,89]

- Soy: Miso, tempeh, natto (if soy is tolerated)

- Beverages: Kombucha, water kefir*

- Dairy-free options: Coconut yogurt, coconut kefir

*go easy on Kombucha as tolerance varies.

Why they help:

- Provide live probiotics that can colonize the gut[111,112]

- Fermentation pre-digests foods, making nutrients more bioavailable

- Create beneficial postbiotic compounds

- Support microbial diversity — a key marker of gut health[110,113]

Why to proceed carefully with IBD:

- If you have severe dysbiosis, introducing probiotics too quickly can cause a temporary flare of symptoms (die-off reaction)

- Histamine-sensitive individuals may react to fermented foods[114]

- Some fermented foods are high in FODMAPs[62]

Probiotics in general might* be more beneficial to people with ulcerative colitis[115,116,117,118]. Some research suggests a lower diversity microbiome in Crohn’s disease is associated with a lower disease state.

Remember that different probiotics will work differently with specific diagnosis and manifestations of IBD (Crohn’s, ulcerative colitis, microscopic colitis, indeterminate colitis)[115,119,120].

The smart approach:

- Start with the juice: Begin with 1-2 tablespoons of sauerkraut or kimchi brine before eating the vegetables themselves

- Go low and slow: Introduce one fermented food at a time

- Build gradually: Work up to 5-7 servings per week as tolerated

- Choose quality: Look for raw, unpasteurized products in the refrigerated section — shelf-stable products have been heat-treated and contain no live cultures

During active flares: You may want to hold off or reduce fermented foods until inflammation calms. These are stability and exploratory phase foods for most people with IBD.

Legumes (with attention to texture)

Legumes are nutrient-dense, high in plant-based protein, fiber, and micronutrients [121]. However, they may cause digestive issues for some due to lectins and oligosaccharides [122,123].

Examples: Lentils, beans, chickpeas (hummus is often well-tolerated)

Key: During flares, blend or puree. Lentil pasta can be a great option. As you heal, whole legumes become more tolerable. Proper preparation (soaking, cooking) reduces antinutrients[124].

*Interesting fact: red lentils are allowed on the Specific Carbohydrate Diet.

Nuts & Seeds: Texture Is Often the Issue

Nuts and seeds are nutritionally dense but their rough texture can be problematic for inflamed intestines[125,126].

Solutions:

- Nut butters: Smooth, easily digestible, retains nutritional benefits

- Nut milks: Gentle way to get nutrients

- Ground/blended: Add to smoothies

- Whole nuts: Reserve for solid remission, chew extremely well

Note: Avoid peanuts (actually a legume) as they’re problematic for many with IBD.

There is a growing number of individuals that believe that nuts, like many other plants, contain specific toxins that cause inflammation. The thinking goes along the lines that people who consume seeds are consuming “plant offspring” that do not want to be consumed given plants are trying to reproduce[122,123]. There is mixed evidence to support this theory, but again, legumes and nuts may be inflammatory for some.

🍯 Healthy Sweeteners (Use in moderation)

Let’s be real: completely eliminating sweetness from your life isn’t sustainable for most people. And it doesn’t have to be. The goal isn’t perfection — it’s choosing sweeteners that offer some nutritional value while minimizing harm.

These natural options provide sweetness along with beneficial compounds:

Sweeteners:

- Raw, unprocessed honey: More than just sugar — contains antioxidants, enzymes, and antimicrobial compounds[127,128]. May support beneficial gut bacteria. Choose local, raw varieties when possible.

- Dates and date paste: Whole food sweetener high in fiber, potassium, and antioxidants[129]. Blend soaked dates into smoothies or use date paste in baking.

- 100% pure maple syrup: Contains manganese, zinc, and unique polyphenols not found in other sweeteners[130].

- Coconut sugar: Lower glycemic index than white sugar and contains small amounts of inulin fiber[131].

Key benefits:

- Provide minerals and antioxidants absent in refined sugar

- Less processed than white sugar or corn syrup

- Can satisfy sweet cravings while offering some nutrition

The reality check: These are still forms of sugar. They will still affect blood sugar levels. Use them mindfully as part of a balanced diet — not as health foods to consume freely. Whole fruits remain the best source of sweetness.

IBD tip: During active flares, even natural sugars may feed problematic bacteria. Focus on getting sweetness from well-tolerated fruits like ripe bananas or cooked apples. As you stabilize, these healthier sweeteners can be reintroduced in moderation.

🤔 Natural Alternative Sweeteners (A “Maybe” for most)

These plant-derived sweeteners offer sweetness without the blood sugar impact of regular sugar. However, their effects on gut health are still being studied, and individual tolerance varies[132].

Options to consider:

- Stevia: Derived from the Stevia rebaudiana plant. Zero calories and doesn’t directly affect blood sugar[133]. May have a slight aftertaste. Some studies suggest potential prebiotic effects, while others raise questions about microbiome impact[134].

- Monk fruit (Luo Han Guo): Derived from a small melon native to Southeast Asia. Zero calories, doesn’t affect blood sugar. Often mixed with other sweeteners due to intense sweetness. Limited research on gut effects, but generally considered safe[135].

- Erythritol: A sugar alcohol with almost zero calories. Doesn’t affect blood sugar or cause tooth decay. Generally well-tolerated, though large amounts may cause digestive upset in some [136].

- Xylitol: Sugar alcohol with 40% fewer calories than sugar. May have dental health benefits. More likely to cause digestive issues than erythritol, especially in larger amounts.

IBD-specific considerations:

- Sugar alcohols (xylitol, erythritol, sorbitol) are FODMAPs and may trigger symptoms in sensitive individuals[62,137]

- Research on artificial and alternative sweeteners’ effects on the gut microbiome is ongoing and sometimes contradictory[132,138]

- If you tolerate these well, they can be useful tools — but they’re not necessary for a healthy diet

Our view: If you’re going to use alternative sweeteners, monk fruit and stevia appear to be the gentlest options for most people with IBD. Introduce any new sweetener gradually and observe your body’s response.

⚠️ A Note on Nightshades*

*It is our view that by and large most people with IBD tolerate Nightshades quite well. Generally, and supported by the research, a small subset of IBD patients may not tolerate Nightshade vegetables[139].

Some vegetables that we prepare as savory foods are botanically fruits — and a subset of these belong to the nightshade family, which can be problematic for some people with IBD and other inflammatory conditions.

Nightshade vegetables include:

- Tomatoes

- Bell peppers (all colors)

- Eggplant

- White potatoes (sweet potatoes are NOT nightshades)

- Chili peppers and paprika

Why some people react: Nightshades contain alkaloids (solanine, capsaicin) and lectins that may trigger inflammation or gut irritation in sensitive individuals[140,141]. This doesn’t mean nightshades are “bad” — many people tolerate them perfectly well, and they’re nutrient-dense foods.

How to know if you’re sensitive:

- Track symptoms after consuming nightshade-heavy meals

- Consider a 2-3 week elimination, then systematic reintroduction

- Cooking reduces alkaloid content — raw tomatoes may be more problematic than cooked

Non-nightshade alternatives:

- Instead of tomatoes: Beets (for color), olive tapenade, pesto

- Instead of bell peppers: Zucchini, celery, cucumber

- Instead of white potatoes: Sweet potatoes, parsnips, turnips

What’s safe: Squash, zucchini, pumpkin, cucumber, and avocado — while botanically fruits — are NOT nightshades and are generally very well-tolerated.

Foods to Consider Eliminating

Regardless of where you are in your healing journey, these foods offer no nutritional benefit and often cause harm:

Trans Fats and Ultra-Processed Foods

Trans fat doesn’t occur in large quantities in nature because it’s chemically stabilized and extremely hard for the body to process. It increases LDL, decreases HDL, impairs endothelial function, increases obesity risk, and promotes significant inflammation[142,143,144,145].

Avoid: Store-bought baked goods, anything containing “partially hydrogenated oil,” refrigerator dough, margarine, fried fast food

Vegetable and Seed Oils

While perhaps not as harmful as trans fats, seed oils are often highly processed, high in omega-6 fatty acids, and can lead to oxidation and production of free radicals[146,147,148].

Avoid: Soybean oil, canola oil, corn oil, sunflower oil, safflower oil, grapeseed oil, cottonseed oil

Healthier alternatives: Olive oil, coconut oil, avocado oil, ghee, animal fats like tallow

Binders, Additives, and Artificial Sweeteners

These can disrupt gut health, trigger inflammation, and have other negative effects[149,150]:

Avoid:

- Emulsifiers: Carrageenan[151,152], guar gum, xanthan gum, polysorbate 80[153,154], maltodextrin[155], carboxymethylcellulose[156,157]

- Artificial colors: Red #40[158], Yellow #5, Blue #1, caramel color

- Preservatives: Sodium benzoate, sodium nitrates, BHA, BHT

- Artificial sweeteners: Aspartame, sucralose [159,160], saccharin[138]

The Adaptive Dietary Framework: Your Personalized Approach

The IBD Food Pyramid provides general guidance, but your specific diet will be unique to you. That’s where our Adaptive Dietary Framework (ADF) comes in.

Unlike other diets, the ADF doesn’t condemn foods to permanent “legal” or “illegal” status. Instead, it provides a nuanced perspective that foods can impact us differently depending on context and our internal biology[1,9]. The state of your microbiome, level of inflammation, and psychological state all color your relationship with food.

The Three Phases

Foundational Phase (Acute Symptoms) During flares or high disease activity, focus on:

- Nutrient-dense, minimally processed foods [5,7]

- Soft, pureed, easily digestible textures [55,56]

- Anti-inflammatory foods from the top tiers

- Elimination of known triggers

- Probiotic and prebiotic-rich foods (start slowly) [110,115]

Stability Phase (Resilience Building) As symptoms improve:

- Gradually reintroduce foods from all tiers

- Expand textures

- Test “Maybe” foods one at a time

- Continue emphasizing whole, unprocessed foods

- Build your personalized “Yes” food list

Exploratory Phase (Expansion) When you’re stable:

- Strategic dietary experimentation

- Navigate social dining with more flexibility

- Gauge your body’s responses

- Balance physical health with mental well-being

- Reduce the stress of continuous dietary vigilance

“Yes,” “Maybe,” and “No” Foods

We don’t believe in labeling foods as “good” or “bad.” That language carries moral weight that doesn’t belong in your relationship with food [10].

“Yes” foods are foods you enjoy that generally work well for your body. Your staples and fallbacks.

“Maybe” foods have varied impacts. Sometimes fine, sometimes not. These deserve ongoing experimentation with attention to context.

“No” foods are foods you almost always avoid because they consistently exacerbate your symptoms.

One person’s “Yes” food may be another person’s firm “No.” There’s nothing morally superior about either approach if each person is addressing their authentic lived truth.

When, Where, and How You Eat

Timing Matters

- Some people do best with 2 meals per day with fasting time between [161,162]

- Others need smaller, more frequent meals

- Many benefit from not eating close to bedtime

- Experiment with meal timing; your gut needs rest periods to heal [163]

Where You Eat

We recommend preparing a large portion of your meals at home. Restaurant food often contains inflammatory oils, hidden additives, and excessive salt [7,8]. When dining out, aim for high-quality restaurants, not fast food.

If preparing meals is new to you, start small. Aim to prepare one meal per day at home and gradually increase.

How You Eat

The physiological and psychological state at the time of eating plays a role in your body’s ability to digest effectively [164,165].

- Eat intentionally: Chew very well, take time between bites

- Avoid multitasking: Turn off screens during meals

- Eat calmly: Stress activates inflammatory pathways [166,167]

See if you notice a difference in your body or mood after eating this way.

Choosing Your Starting Point

Step 1. Select an introductory dietary strategy as a starting point for your Adaptive Dietary Framework. Your ADF can combine several dietary strategies together. We’ve detailed the most popular, science-based options below:

| Diet | Condition Domain | Pros | Cons |

| SCD [94,95,96] | Gut-Microbiome | Lengthy history; Popular with good results | Often too restrictive to be realistic; Doesn’t prioritize microbiome; May be too heavy on animal products & dairy for some |

| AIP [168,169] | Immune-Inflammation, Gut-Microbiome | Popular with good results; Large community of support & resources | Restricts some foods (e.g. nightshades) that may be beneficial; Philosophy of restriction |

| IBD-AID [170] | Gut-Microbiome, Immune-Inflammation | Developed specifically for IBD at UMass; Phased approach aligns with ADF; Emphasizes prebiotics and probiotics | Less well-known; Fewer community resources |

| CDED [171,172] | Gut-Microbiome, Immune-Inflammation | Strong clinical evidence; Designed for Crohn’s specifically | Requires partial enteral nutrition |

| Mediterranean [94,173] | Immune-Inflammation, Gut-Microbiome, Lifestyle-Metabolic | Least restrictive; May be as effective as SCD in studies | Permits gluten and other common triggers |

| Low-FODMAP [62,63,64] | Gut-Microbiome | Effective for IBS symptoms; Helps identify bothersome foods | Complex and restrictive; Temporary solution |

| Plant-Forward | Lifestyle-Metabolic, Health Optimization | Emphasizes plants without eliminating animal products; Flexible | May not provide enough protein for some |

| Animal-Forward | Immune-Inflammation, Gut-Microbiome | Emphasizes nutrient-dense animal foods; High-quality protein | May lack fiber diversity if plants minimized |

The DINE-CD trial found that both the Specific Carbohydrate Diet and Mediterranean diet achieved similar remission rates (about 46%) in adults with Crohn’s disease [94]. However, there were multiple problems with study design and some experts point out that SCD, likely done in a more intentional way, would have been superior to Mediterranean. Both improved symptoms and quality of life.

Step 2. Combine what you already know about your dietary tolerances with your selected introductory diet to add functional food categories to your ADF and describe the context of each food category for your current phase.

Step 3. As you proceed through your day-to-day life, pay attention to the relationship between foods, your symptoms, and how you feel. Add and revise more contexts for different foods for each phase, and continue to build your ADF slowly as you learn more.

The Bottom Line

The IBD Food Pyramid provides a visual framework for gut-friendly eating, but it’s a starting point, not a rigid prescription.

What we know from the research:

- A Mediterranean-style diet benefits most patients with IBD [5,94,173]

- Texture modification protects healing tissue while maintaining nutrition [55,56]

- Fermented foods increase microbiome diversity and decrease inflammatory markers [110]

- Strategic carbohydrate modulation helps many people with IBD [94,95,96]

- Ultra-processed foods, seed oils, and artificial additives promote inflammation [7,149,150]

- Individual responses vary; you must discover what works for your body [1,9]

You have wounds inside you. Feed them gently. Give them what they need to heal.

And know that remission is possible. I’ve seen it hundreds of times. With the right approach, the right support, and the right mindset, you can reclaim your health.

This information is for educational purposes only and is not medical advice. Always consult your healthcare provider before making changes to your treatment plan. Individual results vary. Systema Health coaching complements medical care and does not replace it.

Ready to build your personalized food pyramid? Our Adaptive Dietary Framework provides a comprehensive approach to discovering your optimal diet. [Learn more about Systema IBD →]

References

[1] Levine A, Rhodes JM, Lindsay JO, et al. Dietary Guidance From the International Organization for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(6):1381-1392.

[2] Aldars-García L, Chaparro M, Gisbert JP. Systematic Review: The Gut Microbiome and Its Potential Clinical Application in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Microorganisms. 2021;9(5):977.

[3] Shan Y, Lee M, Chang EB. The Gut Microbiome and Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Annu Rev Med. 2022;73:455-468.

[4] Qiu P, Ishimoto T, Fu L, et al. The Gut Microbiota in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:733992.

[5] Hashash JG, Elkins J, Lewis JD, Binion DG. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Diet and Nutritional Therapies in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Expert Review. Gastroenterology. 2024;166(3):521-532.

[6] Bischoff SC, Bager P, Escher J, et al. ESPEN guideline on Clinical Nutrition in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Nutr. 2023;42(3):352-379.

[7] Forbes A, Escher J, Hébuterne X, et al. ESPEN guideline: Clinical nutrition in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Nutr. 2017;36(2):321-347.

[8] Bischoff SC, Escher J, Hébuterne X, et al. ESPEN practical guideline: Clinical Nutrition in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Nutr. 2020;39(3):632-653.

[9] Rubin DT, Ananthakrishnan AN, Siegel CA, et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Ulcerative Colitis in Adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(3):384-413.

[10] Collins SM. Interrogating the Gut-Brain Axis in the Context of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Translational Approach. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26(4):493-501.

[11] Lichtenstein GR, Loftus EV Jr, Isaacs KL, et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Management of Crohn’s Disease in Adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(4):481-517.

[12] Svolos V, Gordon H, Lomer MCE, et al. ECCO Consensus on Dietary Management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2025;19(9):jjaf122.

[13] Balestrieri P, Ribolsi M, Guarino MPL, et al. Nutritional Aspects in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Nutrients. 2020;12(2):372.

[14] Vidal-Lletjós S, Beaumont M, Tomé D, et al. Therapeutic Potential of Amino Acids in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Nutrients. 2017;9(9):920.

[15] Rao R, Samak G. Role of Glutamine in Protection of Intestinal Epithelial Tight Junctions. J Epithel Biol Pharmacol. 2012;5(Suppl 1-M7):47-54.

[16] Benjamin J, Makharia G, Ahuja V, et al. Glutamine and Whey Protein Improve Intestinal Permeability and Morphology in Patients with Crohn’s Disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57(4):1000-1012.

[17] Nguyen GC, Munsell M, Harris ML. Nationwide prevalence and prognostic significance of clinically diagnosable protein-calorie malnutrition in hospitalized inflammatory bowel disease patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14(8):1105-1111.

[18] Massironi S, Viganò C, Palermo A, et al. Inflammation and malnutrition in inflammatory bowel disease. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8(6):579-590.

[19] Ryan E, McNicholas D, Creavin B, et al. Sarcopenia and Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25(1):67-73.

[20] Nardone OM, de Sire R, Petito V, et al. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases and Sarcopenia: The Role of Inflammation and Gut Microbiota. Front Immunol. 2021;12:694217.

[21] Marton LT, Goulart RA, de Carvalho ACA, Barbalho SM. Omega Fatty Acids and Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: An Overview. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(19):4851.

[22] Scaioli E, Sartini A, Bellanova M, et al. Eicosapentaenoic Acid Reduces Fecal Levels of Calprotectin and Prevents Relapse in Patients With Ulcerative Colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(8):1268-1275.

[23] Calder PC. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and inflammatory processes: nutrition or pharmacology? Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;75(3):645-662.

[24] Calder PC. Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Inflammatory Processes. Nutrients. 2010;2(3):355-374.

[25] Turner D, Shah PS, Steinhart AH, et al. Maintenance of remission in inflammatory bowel disease using omega-3 fatty acids: A systematic review and meta-analyses. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17(1):336-345.

[26] Ananthakrishnan AN, Khalili H, Konijeti GG, et al. Long-term intake of dietary fat and risk of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2014;63(5):776-784.

[27] Ye Z, Zhang C, Wang S, et al. CDP-choline modulates cholinergic signaling and gut microbiota to alleviate DSS-induced inflammatory bowel disease. Biochem Pharmacol. 2023;217:115804.

[28] Chen Q, Chen O, Martins IM, et al. Collagen peptides ameliorate intestinal epithelial barrier dysfunction in immunostimulatory Caco-2 cell monolayers via enhancing tight junctions. Food Funct. 2017;8(3):1144-1151.

[29] Tsune I, Ikejima K, Hirose M, et al. Dietary glycine prevents chemical-induced experimental colitis in the rat. Gastroenterology. 2003;125(3):775-785.

[30] Chen J, Yang Y, Yang Y, et al. Dietary Supplementation with Glycine Enhances Intestinal Mucosal Integrity and Ameliorates Inflammation in C57BL/6J Mice with High-Fat Diet-Induced Obesity. J Nutr. 2021;151(7):1769-1778.

[31] Zhou Q, Verne ML, Fields JZ, et al. Randomised placebo-controlled trial of dietary glutamine supplements for postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2019;68(6):996-1002.

[32] Cabré E, Mañosa M, Gassull MA. Omega-3 fatty acids and inflammatory bowel diseases – a systematic review. Br J Nutr. 2012;107(S2):S240-S252.

[33] Hawthorne AB, Daneshmend TK, Hawkey CJ, et al. Treatment of ulcerative colitis with fish oil supplementation: a prospective 12 month randomised controlled trial. Gut. 1992;33(7):922-928.

[34] Beauchamp GK, Keast RSJ, Morel D, et al. Phytochemistry: ibuprofen-like activity in extra-virgin olive oil. Nature. 2005;437(7055):45-46.

[35] Parkinson L, Keast R. Oleocanthal, a Phenolic Derived from Virgin Olive Oil: A Review of the Beneficial Effects on Inflammatory Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15(7):12323-12334.

[36] Kouka P, Tekos F, Valta K, et al. Effects of olive oil and its components on intestinal inflammation and inflammatory bowel disease. Nutrients. 2022;14(4):875.

[37] Thompson SV, Bailey MA, Taylor AM, et al. Avocado Consumption Alters Gastrointestinal Bacteria Abundance and Microbial Metabolite Concentrations among Adults with Overweight or Obesity. J Nutr. 2021;151(4):753-762.

[38] Li Z, Kravitz S, Henning SM, et al. Impact of daily avocado consumption on gut microbiota in adults with abdominal obesity. Food Funct. 2025.

[39] Leeuwendaal NK, Stanton C, O’Toole PW, Beresford TP. The effects of dairy and dairy derivatives on the gut microbiota: a systematic literature review. Gut Microbes. 2020;12(1):1799533.

[40] Belluzzi A, Brignola C, Campieri M, et al. Effect of an enteric-coated fish-oil preparation on relapses in Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(24):1557-1560.

[41] Millman JF, Okamoto S, Teruya T, et al. Extra-virgin olive oil and the gut-brain axis: influence on gut microbiota, mucosal immunity, and cardiometabolic and cognitive health. Nutr Rev. 2021;79(12):1362-1387.

[42] Li S, Wu B, Fu W, Reddivari L. The Anti-inflammatory Effects of Dietary Anthocyanins against Ulcerative Colitis. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(10):2588.

[43] Osman N, Adawi D, Ahrné S, et al. Bilberries and their anthocyanins ameliorate experimental colitis. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2011;55(12):1773-81.

[44] Rodríguez-Daza MC, Daoust L, Boutkrabt L, et al. Wild blueberry proanthocyanidins shape distinct gut microbiota profile and influence glucose homeostasis. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):2217.

[45] Cladis DP, Simpson AMR, Cooper KJ, et al. Blueberry polyphenols alter gut microbiota & phenolic metabolism in rats. Food Funct. 2021;12(5):2442-2456.

[46] Morissette A, Kropp C, Songpadith JP, et al. Blueberry proanthocyanidins and anthocyanins improve metabolic health through a gut microbiota-dependent mechanism in diet-induced obese mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2020;318(6):E965-E980.

[47] Singh R, Chandrashekharappa S, Bodduluri SR, et al. Enhancement of the gut barrier integrity by a microbial metabolite through the Nrf2 pathway. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):89.

[48] Kim H, Banerjee N, Ivanov I, et al. Pomegranate Extract Improves Colitis in IL-10 Knockout Mice Fed a High Fat High Sucrose Diet. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2019;63(12):1800799.

[49] Ruiz-Iglesias P, Massot-Cladera M, Castellote C, et al. Dietary (Poly)phenols and the Gut–Brain Axis in Ageing. Nutrients. 2024;16(10):1500.

[50] Espín JC, Larrosa M, García-Conesa MT, Tomás-Barberán F. Biological significance of urolithins, the gut microbial ellagic acid-derived metabolites. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:270418.

[51] Larrosa M, González-Sarrías A, Yáñez-Gascón MJ, et al. Anti-inflammatory properties of a pomegranate extract and its metabolite urolithin-A in a colitis rat model. J Nutr Biochem. 2010;21(8):717-725.

[52] Hale LP, Greer PK, Trinh CT, Gottfried MR. Treatment with oral bromelain decreases colonic inflammation in the IL-10-deficient murine model of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Immunol. 2005;116(2):135-142.

[53] Zhou Z, Wang L, Feng P, et al. Inhibition of Epithelial TNF-α Receptors by Purified Fruit Bromelain Ameliorates Intestinal Inflammation and Barrier Dysfunction in Colitis. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1468.

[54] Rabbani GH, Teka T, Saha SK, et al. Green banana and pectin improve small intestinal permeability and reduce fluid loss in Bangladeshi children with persistent diarrhea. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49(3):475-484.

[55] Kuang R, Binion DG. The Evolving Guidelines on Fiber Intake for Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease; From Exclusion to Texture Modification. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2025.

[56] Peters V, Dijkstra G, Campmans-Kuijpers MJE. Are all dietary fibers equal for patients with inflammatory bowel disease? A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Nutr Rev. 2022;80(5):1179-1193.

[57] Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation. What Should I Eat with Crohn’s or Colitis? IBD Diet Guide. 2024.

[58] Slavin J. Fiber and prebiotics: Mechanisms and health benefits. Nutrients. 2013;5(4):1417-1435.

[59] Dhingra D, Michael M, Rajput H, Patil RT. Dietary fibre in foods: a review. J Food Sci Technol. 2012;49(3):255-266.

[60] Vandeputte D, Falony G, Vieira-Silva S, et al. Prebiotic inulin-type fructans induce specific changes in the human gut microbiota. Gut. 2017;66(11):1968-1974.

[61] Chen K, Xie K, Liu Z, et al. Preventive Effects and Mechanisms of Garlic on Dyslipidemia and Gut Microbiome Dysbiosis. Nutrients. 2019;11(6):1225.

[62] Cox SR, Lindsay JO, Fromentin S, et al. Effects of Low FODMAP Diet on Symptoms, Fecal Microbiome, and Markers of Inflammation in Patients With Quiescent Inflammatory Bowel Disease in a Randomized Trial. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(1):176-188.e7.

[63] Pedersen N, Ankersen DV, Felding M, et al. Low-FODMAP diet reduces irritable bowel symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(18):3356-3366.

[64] Zhan YL, Zhan YA, Dai SX. Is a low FODMAP diet beneficial for patients with inflammatory bowel disease? A meta-analysis and systematic review. Clin Nutr. 2018;37(1):123-129.

[65] Liu H, Liu M, Fu X, et al. Gut microbiota regulation and anti-inflammatory effect of β-carotene in dextran sulfate sodium-stimulated ulcerative colitis in rats. J Food Sci. 2021;86(5):2083-2093.

[66] Wang Y, Do T, Marshall LJ, Boesch C. Effect of two-week red beetroot juice consumption on modulation of gut microbiota in healthy human volunteers – A pilot study. Food Chem. 2023;404:134989.

[67] Zhang X, Yang Y, Wu Z, Weng P. The modulatory effect of anthocyanins from purple sweet potato on human intestinal microbiota in vitro. J Agric Food Chem. 2016;64(12):2582-2590.

[68] Wedlake L, Slack N, Andreyev HJN, Whelan K. Fiber in the treatment and maintenance of inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20(3):576-586.

[69] Zhang T, Holman J, McKinstry D, et al. A steamed broccoli sprout diet preparation that reduces colitis via the gut microbiota. J Nutr Biochem. 2023;112:109215.

[70] Holman JM, Colucci L, Baudewyns D, et al. Steamed broccoli sprouts alleviate DSS-induced inflammation and retain gut microbial biogeography in mice. mSystems. 2023;8(3):e00532-23.

[71] Yanaka A, Fahey JW, Fukumoto A, et al. Dietary sulforaphane-rich broccoli sprouts reduce colonization and attenuate gastritis in Helicobacter pylori-infected mice and humans. Cancer Prev Res. 2009;2(4):353-360.

[72] Jayachandran M, Chen J, Chung SSM, Xu B. A critical review on the impacts of β-glucans on gut microbiota and human health. J Nutr Biochem. 2018;61:101-110.

[73] Akramienė D, Kondrotas A, Didžiapetrienė J, Kevelaitis E. Effects of beta-glucans on the immune system. Medicina (Kaunas). 2007;43(8):597-606.

[74] Vetvicka V, Vetvickova J. Immune-enhancing effects of Maitake and Shiitake extracts. Ann Transl Med. 2014;2(2):14.

[75] Dai X, Stanilka JM, Rowe CA, et al. Consuming Lentinula edodes (Shiitake) Mushrooms Daily Improves Human Immunity. J Am Coll Nutr. 2015;34(6):478-487.

[76] Nishitani Y, Zhang L, Miyamura K, et al. Intestinal anti-inflammatory activity of lentinan. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e62921.

[77] Diling C, et al. Extracts from Hericium erinaceus relieve inflammatory bowel disease by regulating immunity and gut microbiota. Oncotarget. 2017;8(49):85838-85857.

[78] Ratto D, Corana F, Mannucci B, et al. Hericium erinaceus Extract Exerts Beneficial Effects on Gut–Neuroinflammaging–Cognitive Axis in Elderly Mice. Biology. 2023;13(1):18.

[79] Guo C, Guo D, Fang L, et al. Ganoderma lucidum polysaccharide modulates gut microbiota and immune cell function to inhibit inflammation and tumorigenesis in colon. Carbohydr Polym. 2021;267:118231.

[80] Pallav K, Dowd SE, Villafuerte J, et al. Effects of polysaccharopeptide from Trametes versicolor and amoxicillin on the gut microbiome of healthy volunteers. Gut Microbes. 2014;5(4):458-467.

[81] Saleh MH, Rashedi I, Keating A. Immunomodulatory Properties of Coriolus versicolor: The Role of Polysaccharopeptide. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1087.

[82] Szilagyi A, Galiatsatos P, Xue X. Systematic review and meta-analysis of lactose digestion, its impact on intolerance and nutritional effects of dairy food restriction in inflammatory bowel diseases. Nutr J. 2016;15:67.

[83] Eadala P, Matthews SB, Waud JP, et al. Association of lactose sensitivity with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34(7):735-46.

[84] Ratajczak AE, Rychter AM, Zawada A, et al. Lactose intolerance in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases and dietary management in prevention of osteoporosis. Nutrition. 2021;82:111043.

[85] Mishkin B, Yalovsky M, Mishkin S. Association between Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Lactose Intolerance. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2020;76(4):169-176.

[86] Park YW, Juárez M, Ramos M, Haenlein GFW. Physico-chemical characteristics of goat and sheep milk. Small Rumin Res. 2007;68(1-2):88-113.

[87] Milan AM, Shrestha A, Karlström HJ, et al. Milk Containing A2 β-Casein ONLY Causes Fewer Symptoms of Lactose Intolerance. Nutrients. 2020;12(12):3855.

[88] Yılmaz İ, Dolar ME, Özpınar H. Effect of administering kefir on the changes in fecal microbiota and symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2019;30(3):242-253.

[89] Savaiano DA, Hutkins RW. Yogurt, cultured fermented milk, and health: a systematic review. Nutr Rev. 2021;79(5):599-614.

[90] Jianqin S, Leiming X, Lu X, et al. Effects of milk containing only A2 beta casein versus milk containing both A1 and A2 beta casein proteins on gastrointestinal physiology. Nutr J. 2016;15:35.

[91] Ho S, Woodford K, Kukuljan S, Pal S. Comparative effects of A1 versus A2 beta-casein on gastrointestinal measures. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2014;68(9):994-1000.

[92] Ferreira P, Cravo M, Guerreiro CS, et al. Influence of Diet on the Course of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62(8):2087-2094.

[93] Ananthakrishnan AN, Khalili H, Konijeti GG, et al. A prospective study of long-term intake of dietary fiber and risk of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2013;145(5):970-977.

[94] Lewis JD, Sandler RS, Brotherton C, et al. A Randomized Trial Comparing the Specific Carbohydrate Diet to a Mediterranean Diet in Adults With Crohn’s Disease. Gastroenterology. 2021;161(3):837-852.e9.

[95] Suskind DL, Lee D, Kim YM, et al. The Specific Carbohydrate Diet and Diet Modification as Induction Therapy for Pediatric Crohn’s Disease. Nutrients. 2020;12(12):3749.

[96] Cohen SA, Gold BD, Oliva S, et al. Clinical and Mucosal Improvement With Specific Carbohydrate Diet in Pediatric Crohn Disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;59(4):516-521.

[97] Rizzello CG, Portincasa P, Montemurro M, et al. Sourdough Fermented Breads are More Digestible than Those Started with Baker’s Yeast Alone. Nutrients. 2019;11(12):2954.

[98] Gobbetti M, De Angelis M, Di Cagno R, et al. Feeding with Sustainably Sourdough Bread Has the Potential to Promote the Healthy Microbiota Metabolism at the Colon Level. Microbiol Spectr. 2021;9(3):e0049421.

[99] Boakye PG, Kougblenou I, Murai T, et al. Impact of sourdough fermentation on FODMAPs and amylase-trypsin inhibitor levels in wheat dough. J Cereal Sci. 2022;108:103574.

[100] Dhital S, Gidley MJ, Warren FJ. Resistant starch: impact on the gut microbiome and health. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2020;61:31-38.

[101] Maier TV, Lucio M, Lee LH, et al. Impact of Dietary Resistant Starch on the Human Gut Microbiome, Metaproteome, and Metabolome. mBio. 2017;8(5):e01343-17.

[102] Ni Y, Qian L, Siliceo SL, et al. Resistant starch intake facilitates weight loss in humans by reshaping the gut microbiota. Nat Metab. 2024;6(2):578-597.

[103] Catassi C, Elli L, Bonaz B, et al. Non-Celiac Wheat Sensitivity: An Immune-Mediated Condition with Systemic Manifestations. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2019;48(1):165-182.

[104] Catassi C, et al. Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity: The New Frontier of Gluten Related Disorders. Nutrients. 2013;5(10):3839-3853.

[105] Weaver KN, Herfarth HH. Gluten-Free Diet in IBD: Time for a Recommendation? Mol Nutr Food Res. 2021;65(5):e1901274.

[106] Herfarth HH, et al. Prevalence of a gluten-free diet and improvement of clinical symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20(7):1194-1197.

[107] Lopes EW, Lebwohl B, Burke KE, et al. Dietary Gluten Intake Is Not Associated With Risk of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in US Adults Without Celiac Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(2):303-313.e6.

[108] Rizzello CG, De Angelis M, Di Cagno R, et al. Highly efficient gluten degradation by lactobacilli and fungal proteases during food processing. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73(14):4499-4507.

[109] Shewry PR, Hey SJ. The contribution of wheat to human diet and health. Food Energy Secur. 2015;4(3):178-202.

[110] Wastyk HC, Fragiadakis GK, Perelman D, et al. Gut-microbiota-targeted diets modulate human immune status. Cell. 2021;184(16):4137-4153.e14.

[111] Marco ML, et al. Health benefits of fermented foods: microbiota and beyond. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2017;44:94-102.

[112] Staudacher HM, Lomer MCE, Farquharson FM, et al. Does consumption of fermented foods modify the human gut microbiota? J Nutr. 2020;150(7):1680-1692.

[113] Dimidi E, et al. Fermented Foods: Definitions and Characteristics, Impact on the Gut Microbiota and Effects on Gastrointestinal Health and Disease. Nutrients. 2019;11(8):1806.

[114] Sánchez-Pérez S, Comas-Basté O, Duelo A, et al. Low-Histamine Diets: Is the Exclusion of Foods Justified by Their Histamine Content? Nutrients. 2021;13(5):1395.

[115] Sood A, Midha V, Makharia GK, et al. The probiotic preparation, VSL#3 induces remission in patients with mild-to-moderately active ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(11):1202-9.

[116] Tursi A, Brandimarte G, Papa A, et al. Treatment of relapsing mild-to-moderate ulcerative colitis with the probiotic VSL#3 as adjunctive to a standard pharmaceutical treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(10):2218-27.

[117] Miele E, Pascarella F, Giannetti E, et al. Effect of a probiotic preparation (VSL#3) on induction and maintenance of remission in children with ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(2):437-43.

[118] Kruis W, Fric P, Pokrotnieks J, et al. Maintaining remission of ulcerative colitis with the probiotic Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 is as effective as with standard mesalazine. Gut. 2004;53(11):1617-23.

[119] Schultz M. Clinical use of E. coli Nissle 1917 in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14(7):1012-8.

[120] Ganji‐Arjenaki M, Rafieian‐Kopaei M. Review of Saccharomyces boulardii as a treatment option in IBD. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2018;40(6):465-475.

[121] Padhi EMT, Ramdath DD. Potential Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Legumes: A Review. Br J Nutr. 2017;117(4):469-489.

[122] Pusztai A. Dietary lectins are metabolic signals for the gut and modulate immune and hormone functions. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1993;47(10):691-699.

[123] Vasconcelos IM, Oliveira JT. Antinutritional properties of plant lectins. Toxicon. 2004;44(4):385-403.

[124] Markiewicz LH, Honke J, Haros M, et al. Diet shapes the ability of human intestinal microbiota to degrade phytate. J Appl Microbiol. 2013;115(1):247-259.

[125] Yu Z, Malik VS, Keum N, et al. Associations between nut consumption and inflammatory biomarkers. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;104(3):722-728.

[126] Lopes EW, Yu Z, Walsh SE, et al. Dietary Nut and Legume Intake and Risk of Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2025;31(9):2458-2466.

[127] Samarghandian S, Farkhondeh T, Samini F. Honey and Health: A Review of Recent Clinical Research. Pharmacogn Res. 2017;9(2):121-127.

[128] Johnston M, McBride M, Dahiya D, et al. Antibacterial activity of Manuka honey and its components: An overview. AIMS Microbiol. 2018;4(4):655-664.

[129] Al-Farsi MA, Lee CY. Nutritional and functional properties of dates: a review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2008;48(10):877-887.

[130] Ball DW. The Chemical Composition of Maple Syrup. J Chem Educ. 2007;84(10):1647.

[131] Trinidad TP, et al. Glycemic index of commonly consumed carbohydrate foods in the Philippines. J Funct Foods. 2010;2(4):271-274.

[132] Ruiz-Ojeda FJ, et al. Effects of Sweeteners on the Gut Microbiota: A Review of Experimental Studies and Clinical Trials. Adv Nutr. 2019;10(suppl_1):S31-S48.

[133] Goyal SK, Samsher, Goyal RK. Stevia (Stevia rebaudiana) a bio-sweetener: a review. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2010;61(1):1-10.

[134] Singh A, Freund P, Gildea M, et al. Consumption of the Non-Nutritive Sweetener Stevia for 12 Weeks Does Not Alter the Composition of the Human Gut Microbiota. Nutrients. 2024;16(2):296.

[135] Gong X, et al. The Fruits of Siraitia grosvenorii: A Review of a Chinese Food-Medicine. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:1400.

[136] Mäkinen KK. Gastrointestinal Disturbances Associated with the Consumption of Sugar Alcohols. Int J Dent. 2016;2016:5967907.

[137] Varney J, et al. FODMAPs: food composition, defining cutoff values and international application. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32(S1):53-61.

[138] Suez J, Korem T, Zeevi D, et al. Artificial sweeteners induce glucose intolerance by altering the gut microbiota. Nature. 2014;514(7521):181-186.

[139] Levine A, Rhodes JM, Lindsay JO, et al. Dietary Guidance From the International Organization for the Study of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(6):1381-1392.

[140] Patel B, Schutte R, Sporns P, et al. Potato glycoalkaloids adversely affect intestinal permeability and aggravate inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2002;8(5):340-346.

[141] Childers NF, Margoles MS. An Apparent Relation of Nightshades (Solanaceae) to Arthritis. J Neurol Orthop Med Surg. 1993;14:227-231.

[142] Mozaffarian D, Katan MB, Ascherio A, et al. Trans Fatty Acids and Cardiovascular Disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(15):1601-1613.

[143] Mozaffarian D. Trans fatty acids – effects on systemic inflammation and endothelial function. Atheroscler Suppl. 2006;7(2):29-32.

[144] Okamura T, Hashimoto Y, Majima S, et al. Trans Fatty Acid Intake Induces Intestinal Inflammation and Impaired Glucose Tolerance. Front Immunol. 2021;12:669672.

[145] Lopez-Garcia E, Schulze MB, Meigs JB, et al. Consumption of trans fatty acids is related to plasma biomarkers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. J Nutr. 2005;135(3):562-566.

[146] Simopoulos AP. The importance of the ratio of omega-6/omega-3 essential fatty acids. Biomed Pharmacother. 2002;56(8):365-379.

[147] Simopoulos AP. The importance of the omega-6/omega-3 fatty acid ratio in cardiovascular disease and other chronic diseases. Exp Biol Med. 2008;233(6):674-688.

[148] Kaliannan K, Wang B, Li XY, et al. A host-microbiome interaction mediates the opposing effects of omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids on metabolic endotoxemia. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11276.

[149] Chassaing B, Koren O, Goodrich JK, et al. Dietary emulsifiers impact the mouse gut microbiota promoting colitis and metabolic syndrome. Nature. 2015;519(7541):92-96.

[150] Chassaing B, Van de Wiele T, De Bodt J, et al. Dietary emulsifiers directly alter human microbiota composition and gene expression ex vivo potentiating intestinal inflammation. Gut. 2017;66(8):1414-1427.

[151] Martino JV, Van Limbergen J, Cahill LE. The Role of Carrageenan and Carboxymethylcellulose in the Development of Intestinal Inflammation. Front Pediatr. 2017;5:96.

[152] Tobacman JK. Review of harmful gastrointestinal effects of carrageenan in animal experiments. Environ Health Perspect. 2001;109(10):983-994.

[153] Ogulur I, Pat Y, Ardicli O, et al. Mechanisms of gut epithelial barrier impairment caused by food emulsifiers polysorbate 20 and polysorbate 80. Allergy. 2023;78(9):2441-2455.

[154] Viennois E, Merlin D, Gewirtz AT, Chassaing B. Dietary emulsifier–induced low-grade inflammation promotes colon carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2017;77(1):27-40.

[155] Nickerson KP, McDonald C. Crohn’s Disease-Associated Adherent-Invasive Escherichia coli Adhesion Is Enhanced by Exposure to the Ubiquitous Dietary Polysaccharide Maltodextrin. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(12):e52132.

[156] Chassaing B, Compher C, Bonhomme B, et al. Randomized Controlled-Feeding Study of Dietary Emulsifier Carboxymethylcellulose Reveals Detrimental Impacts on the Gut Microbiota and Metabolome. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(3):743-756.

[157] Naimi S, Viennois E, Gewirtz AT, Chassaing B. Direct impact of commonly used dietary emulsifiers on human gut microbiota. Microbiome. 2021;9(1):66.

[158] Kwon YH, Banskota S, Wang H, et al. Chronic exposure to synthetic food colorant Allura Red AC promotes susceptibility to experimental colitis via intestinal serotonin in mice. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):7617.

[159] Bian X, Chi L, Gao B, et al. Gut Microbiome Response to Sucralose and Its Potential Role in Inducing Liver Inflammation in Mice. Front Physiol. 2017;8:487.

[160] Méndez-García LA, Bueno-Hernández N, Cid-Soto MA, et al. Ten-Week Sucralose Consumption Induces Gut Dysbiosis and Altered Glucose and Insulin Levels in Healthy Young Adults. Microorganisms. 2022;10(2):434.

[161] Rangan P, Choi I, Wei M, et al. Fasting-Mimicking Diet Modulates Microbiota and Promotes Intestinal Regeneration to Reduce Inflammatory Bowel Disease Pathology. Cell Rep. 2019;26(10):2704-2719.e6.

[162] Lavallee CM, Bruno A, Ma C, et al. A Review of the Role of Intermittent Fasting in the Management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2023;16:17562848231171756.

[163] Mihaylova MM, Cheng CW, Cao AQ, et al. Fasting Activates Fatty Acid Oxidation to Enhance Intestinal Stem Cell Function during Homeostasis and Aging. Cell Stem Cell. 2018;22(5):769-778.e4.

[164] Cherpak CE. Mindful Eating: A Review Of How The Stress-Digestion-Mindfulness Triad May Modulate And Improve Gastrointestinal And Digestive Function. Integr Med (Encinitas). 2019;18(4):48-53.

[165] Murray CDR, Flynn J, Ratcliffe L, et al. Effect of acute physical and psychological stress on gut autonomic innervation in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2004;127(6):1695-1703.

[166] Brzozowski B, Mazur-Bialy A, Pajdo R, et al. Mechanisms by which Stress Affects the Experimental and Clinical Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): Role of Brain-Gut Axis. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2016;14(8):892-900.

[167] Sun Y, Li L, Xie R, et al. Psychological stress in inflammatory bowel disease: Psychoneuroimmunological insights into bidirectional gut–brain communications. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1016578.

[168] Konijeti GG, Kim N, Lewis JD, et al. Efficacy of the Autoimmune Protocol Diet for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(11):2054-2060.

[169] Chandrasekaran A, Groven S, Lewis JD, et al. An Autoimmune Protocol Diet Improves Patient-Reported Quality of Life in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Crohns Colitis 360. 2019;1(3):otz019.

[170] Olendzki BC, Silverstein TD, Persuitte GM, et al. An Anti-Inflammatory Diet as Treatment for Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Case Series Report. Nutr J. 2014;13:5.

[171] Levine A, Wine E, Assa A, et al. Crohn’s Disease Exclusion Diet Plus Partial Enteral Nutrition Induces Sustained Remission in a Randomized Controlled Trial. Gastroenterology. 2019;157(2):440-450.e8.

[172] Yanai H, Levine A, Hirsch A, et al. The Crohn’s Disease Exclusion Diet for Induction and Maintenance of Remission in Adults with Mild-to-Moderate Crohn’s Disease (CDED-AD). Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7(1):49-59.

[173] El Amrousy D, Elashry H, Salamah A, et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet Improved Clinical Scores and Inflammatory Markers in Children with Active Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Inflamm Res. 2022;15:2075-2086.